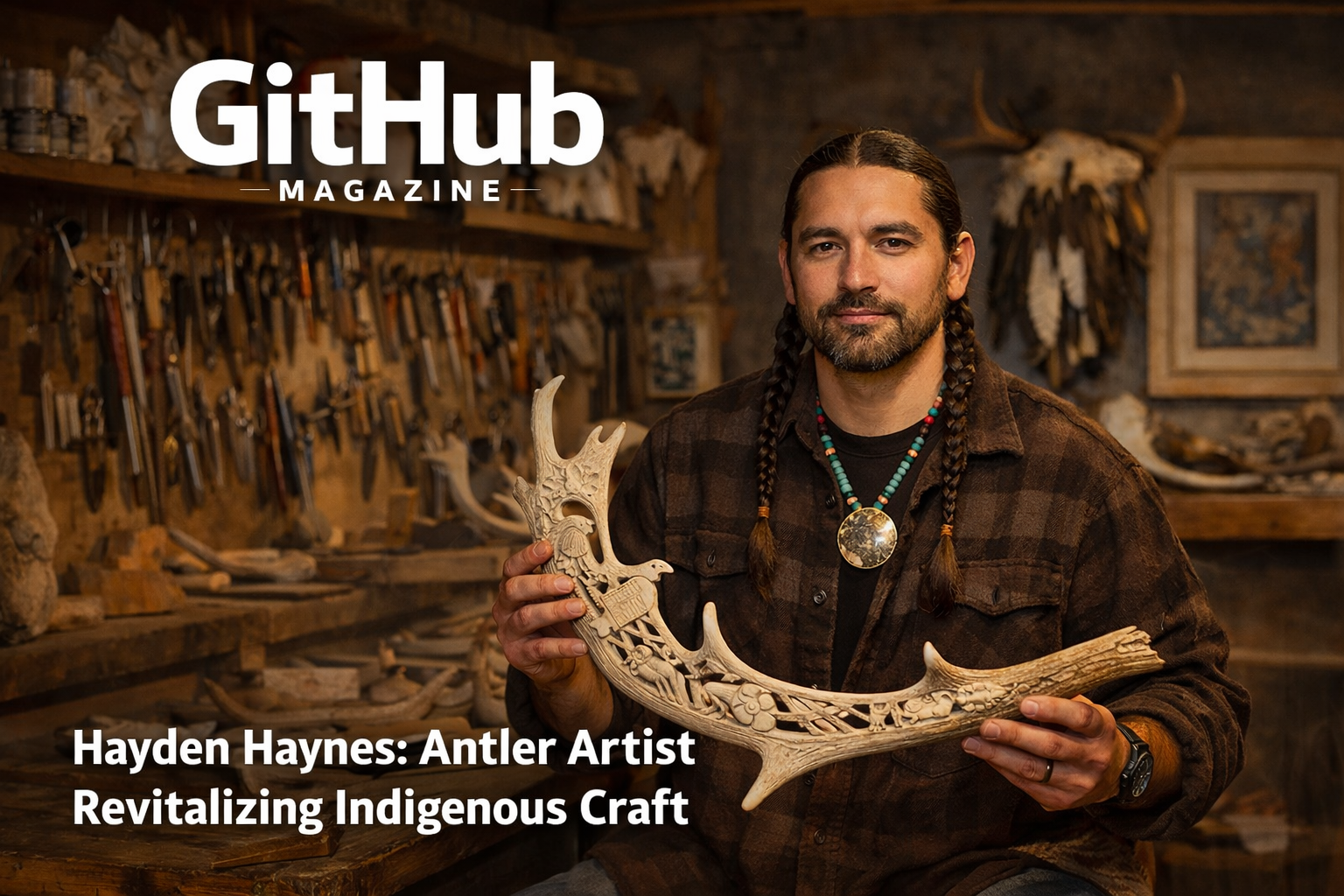

Hayden Haynes: Seneca Antler Artist Reviving Indigenous Craft

Hayden Haynes is a Seneca Nation artist whose antler carvings have become quiet but powerful ambassadors of Indigenous cultural continuity. In museums from New York to Boston, his work appears at first glance to be purely sculptural: smooth curves, finely etched symbols, patient symmetry. But within minutes, viewers realize they are encountering something more layered. His art answers a question many people now search for: who is Hayden Haynes, and why does his work matter in the present moment?

In the first hundred words of any description, the answer becomes clear. Haynes is not only an artist; he is a cultural practitioner who treats material as memory. Antler, for him, is not decorative substance but inherited language. Through it, he translates stories of land, clan, animals, and survival into contemporary form. His career reflects a broader movement in Indigenous art that refuses to let tradition remain frozen behind museum glass.

Raised on Seneca land in western New York, Haynes learned early that craft could be both livelihood and responsibility. Over time, his carvings entered major public collections, his teaching expanded into formal residencies, and his voice joined national conversations about Indigenous sovereignty in art. His work now circulates not just as objects of beauty but as evidence that tradition can evolve without losing its center. In a digital age crowded with disposable imagery, his practice remains slow, tactile, and rooted, insisting that some stories must be carved patiently to endure.

Early Life and Cultural Foundations

Hayden Haynes was born in Claremore, Oklahoma, and grew up on the Seneca-Cattaraugus territory in western New York as a member of the Seneca Nation’s Deer Clan. His childhood environment was defined by extended family, ceremonies, and the everyday presence of Haudenosaunee culture. These influences shaped not only his worldview but his understanding of materials as meaningful, not neutral.

A small moment redirected his life: his aunt gifted him a Dremel tool when he was young. With it, he began experimenting on antler, an organic material deeply embedded in regional Indigenous craft history. He studied the work of local Seneca carvers such as Norman Jimerson and others whose pieces circulated in community spaces long before galleries showed interest. Over time, he adopted more precise tools, including a Foredom flex-shaft system, refining techniques that balanced traditional motifs with personal experimentation.

Haynes has often described learning as an act of listening rather than inventing. The patterns he carves draw on clan symbols, natural forms, and ancestral design logic. Each piece reflects both apprenticeship and autonomy: shaped by community knowledge, yet unmistakably his own. What emerged was not a revival for nostalgia’s sake but a living practice that treats heritage as something usable, adaptable, and present.

Art as Cultural Dialogue

Haynes’s carvings function as conversations between generations. Antler, once a utilitarian material for tools and ornamentation, becomes in his hands a medium for reflection about survival, land relationships, and identity. Within Haudenosaunee traditions, animals are teachers and relatives, not resources alone. By foregrounding antler in fine-art contexts, Haynes invites viewers into that worldview.

Art historians who study Indigenous contemporary practice often describe his work as “cultural translation.” Dr. Maria Thompson, an art historian focusing on Native material culture, notes that his carvings “occupy the space between archive and living body, insisting that tradition continues through hands, not institutions.” Indigenous studies scholar Robert Fields has similarly observed that antler carries ecological memory, linking species, territory, and human responsibility. Curator Janelle Redcorn frames his work as “embodied storytelling,” arguing that each piece records knowledge systems that are rarely legible to outsiders.

This dialogue matters because Native art has long been framed as historical artifact rather than modern expression. Haynes challenges that boundary quietly. His sculptures do not shout protest, yet their presence inside contemporary museums disrupts the idea that Indigenous creativity belongs to the past. They insist that culture is ongoing labor, not completed chapter.

Major Exhibitions and Recognitions

| Year | Exhibition or Recognition | Institution / Location |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | NYSCA/NYFA Fellowship | New York State Council on the Arts |

| 2022 | “O’nigöëi:yo:h: Thinking in Indian” | University at Buffalo |

| Various | Solo exhibitions | Salamanca and Albany, New York |

| Various | Collection acquisitions | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

These milestones marked Haynes’s transition from regional recognition to national visibility. The fellowship provided financial stability for expanded production, while museum acquisitions signaled institutional validation of antler carving as contemporary fine art rather than ethnographic artifact.

Teaching and Community Engagement

Haynes’s influence extends far beyond galleries. He has consistently described teaching as inseparable from his studio practice. Workshops, community demonstrations, and formal residencies allow him to transmit not just technique but historical context. Participants learn where antler comes from, how it is ethically sourced, and what symbolic meanings accompany specific designs.

In 2024, he joined a Teaching Artist Cohort at the Center for Craft, an initiative that supports artists who combine making with cultural education. The program emphasized curriculum design, community collaboration, and sustainable creative economies. For Haynes, this formalized what he had long practiced informally: the belief that knowledge should circulate horizontally, not be hoarded.

Within Seneca communities, his role is often described as stewardship rather than instruction. Younger artists see in his career a model of how traditional craft can support modern livelihoods without surrendering cultural authority. Outside Indigenous communities, his workshops function as corrective experiences, reframing Native art as contemporary, intellectual, and self-directed.

Museums Holding His Work

| Museum | City | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Seneca-Iroquois National Museum | Salamanca, NY | Cultural heritage institution |

| Iroquois Indian Museum | Howes Cave, NY | Indigenous art preservation |

| New York State Museum | Albany, NY | State historical collection |

| Museum of Fine Arts | Boston, MA | Major national art institution |

| Rochester Museum & Science Center | Rochester, NY | Regional cultural repository |

The presence of his work in these collections places Haynes within a lineage of artists who reshaped museum narratives about Native creativity. Instead of being confined to ethnographic departments, his carvings appear alongside contemporary sculpture, changing how audiences interpret Indigenous production.

Revitalizing Indigenous Craft in the Twenty-First Century

Haynes’s career aligns with broader movements of Indigenous cultural resurgence across North America. Artists increasingly reject the binary between “traditional” and “modern,” arguing that such divisions are colonial inventions. His practice embodies this refusal. He uses power tools but honors ancestral design logic. He exhibits in museums while teaching in community centers.

Antler itself becomes political material in this context. It symbolizes ecological relationships disrupted by industrial extraction and colonial land policies. By centering it, Haynes reasserts Indigenous frameworks of sustainability and reciprocity. His work does not romanticize the past, but it resists narratives that equate progress with erasure.

In this sense, his sculptures are both artworks and arguments. They argue that craft can be intellectual labor, that tradition can be innovative, and that cultural survival is not passive inheritance but active creation.

Takeaways

- Hayden Haynes is a Seneca Nation artist specializing in antler carving rooted in Haudenosaunee traditions.

- His work bridges ancestral techniques and contemporary sculpture.

- Museums collect his carvings as fine art, not ethnographic artifacts.

- Teaching and community workshops form a central part of his practice.

- Experts view his work as cultural dialogue rather than decorative craft.

- Antler functions in his art as both material and historical language.

Conclusion

Hayden Haynes occupies a rare position in contemporary art: respected by institutions, trusted by community, and grounded in material tradition. His carvings do not seek spectacle. They accumulate meaning slowly, through touch, repetition, and careful attention to inherited forms. In doing so, they counter a culture of speed with one of patience.

His career suggests that preservation is not about freezing culture in time but allowing it to breathe in new conditions. Each antler piece carries echoes of ancestors while speaking to modern audiences about responsibility, continuity, and belonging. For readers encountering his name for the first time, the lesson is simple yet demanding: some art is not meant merely to be seen but to be understood as living knowledge. Haynes’s work stands as quiet proof that tradition, when practiced with integrity, remains one of the most contemporary forces available to any society.

FAQs

Who is Hayden Haynes?

He is a Seneca Nation artist known for contemporary antler carving rooted in Haudenosaunee cultural traditions.

What material does he primarily use?

Antler, sometimes combined with other natural materials, forms the core of his sculptural practice.

Where is his work displayed?

His pieces appear in museums such as the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the New York State Museum.

Does he teach antler carving?

Yes. He conducts workshops, residencies, and community classes focused on technique and cultural context.

Why is his work important?

It reframes Indigenous craft as living contemporary art rather than historical artifact.