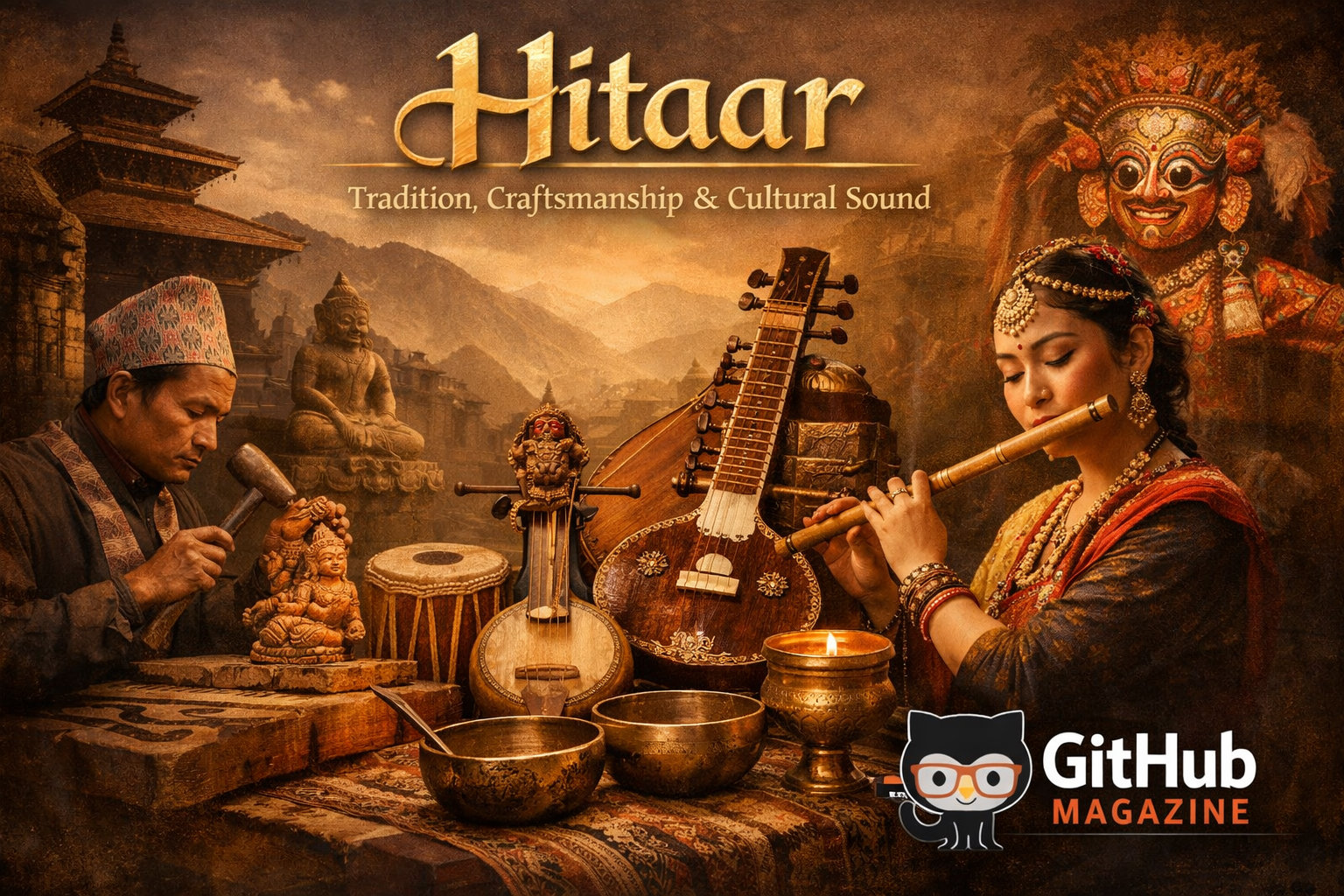

Hitaar Instrument History, Craft and Cultural Meaning

Hitaar is not simply a musical instrument. It is a cultural artifact, a handmade technology of sound, and a vessel of memory that has traveled quietly through centuries of human history. For readers encountering the term for the first time, hitaar refers to a traditional stringed instrument associated with parts of the Middle East and South Asia, known for its warm resonance, handcrafted construction, and deep connection to storytelling, ritual, and community music. Within the first moments of hearing it, listeners often recognize that its sound is neither purely ancient nor entirely modern. It exists in the space between tradition and reinvention.

People searching for hitaar usually want to understand three things: what it is, where it comes from, and why it still matters. The short answer is that hitaar represents a surviving form of musical knowledge passed through generations of artisans and performers, shaped by trade routes, regional aesthetics, and evolving performance practices. It belongs to the same family of human inventions as the lute, the sitar, and the guitar, yet it maintains a distinct voice and cultural function.

In today’s world of algorithmic playlists and digital instruments, hitaar remains grounded in wood, strings, hands, and breath. It appears in village ceremonies, private homes, small performance halls, and increasingly in experimental recordings and fusion music projects. This article examines hitaar not as a curiosity, but as a living system of craft and meaning. From its historical emergence to its modern reinvention, hitaar tells a story that aligns closely with the editorial spirit of Git-Hub Magazine: technology as culture, tradition as innovation, and human creativity as a continuously evolving design.

Historical Origins and Cultural Geography

The origins of hitaar lie in regions where musical knowledge moved along the same routes as spices, textiles, and manuscripts. Long before standardized musical notation or formal conservatories, instruments evolved through imitation, experimentation, and oral instruction. Hitaar emerged from this environment as a hybrid form, influenced by earlier chordophones used across Persia, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Indian subcontinent.

Historical narratives suggest that early versions of hitaar were simpler in structure, often with fewer strings and rougher body carving. As court music developed in regional kingdoms, musicians demanded greater tonal range and stability, encouraging artisans to refine body shape, string tension systems, and fret placement. Over time, the instrument became associated not only with folk performance but also with refined artistic circles, including poets, traveling storytellers, and ceremonial musicians.

Geographically, hitaar never belonged to a single nation-state. Its identity formed across borders that modern maps would later draw. This fluidity helped the instrument survive political shifts and linguistic changes. Where languages transformed and empires rose and fell, the instrument adapted its tuning systems and repertoire while maintaining its essential acoustic character.

In rural areas, hitaar often functioned as a communal object. It was shared among families, repaired repeatedly, and sometimes inherited across generations. In urban centers, more ornate versions appeared, decorated with inlays and crafted from rare woods. Both forms coexisted, reinforcing the idea that hitaar was not defined by luxury or simplicity, but by use.

Anatomy of the Instrument and Traditional Craftsmanship

Every hitaar begins as raw material shaped by human judgment. The most important decision is the selection of wood for the body. Traditional builders favor dense but resonant hardwoods such as rosewood, walnut, or teak. These woods provide durability while allowing sound waves to vibrate fully inside the hollow chamber.

The body is carved manually, often with hand tools passed down through families of instrument makers. The thickness of the wood walls determines volume and tonal warmth. A body carved too thick produces muted sound. Too thin, and the instrument loses structural integrity. Achieving the balance requires experience rather than mathematical measurement.

The neck and fretboard are attached carefully to maintain precise alignment. Frets are positioned according to traditional tuning systems, which differ slightly from Western equal temperament scales. These micro-interval differences give hitaar its recognizable emotional color.

Strings were historically made from animal gut, producing a soft and earthy sound. Modern builders often use metal or synthetic alternatives for stability and longevity. Bridges and tuning pegs are shaped individually, rarely standardized, giving each instrument a subtle acoustic fingerprint.

The making of a single hitaar can take several weeks or months. Builders describe the process as a conversation with the instrument, adjusting shape and tension based on how the wood responds. In this sense, craftsmanship becomes a form of acoustic engineering long before the term existed.

Performance Techniques and Musical Language

Playing hitaar requires both physical discipline and emotional sensitivity. The performer typically sits with the instrument angled across the body, allowing the dominant hand to pluck or strum while the other navigates the frets.

Three main techniques dominate traditional performance: single-string plucking for melodic clarity, multi-string strumming for rhythmic foundation, and fingerpicking patterns that blend melody and rhythm simultaneously. Advanced players manipulate string pressure to create subtle pitch bends, vibrato, and dynamic swells.

Unlike standardized Western instruments, hitaar performance often relies on modal systems learned orally. Students memorize melodic frameworks rather than written scores. Improvisation plays a central role, especially during long-form storytelling performances or ceremonial music.

In ensemble settings, hitaar interacts with percussion instruments and flutes, forming layered textures rather than rigid harmonic structures. The goal is emotional atmosphere rather than technical complexity.

Modern performers increasingly incorporate amplification and effects processing. Some use pickups embedded into the body, allowing the instrument to interface with digital recording systems and live sound equipment. This adaptation has introduced hitaar to experimental genres and contemporary composition without erasing its traditional vocabulary.

Hitaar in Social Life and Ritual Practice

Beyond sound, hitaar functions as a social object. In many communities, its presence marks important moments such as weddings, seasonal festivals, and rites of passage. The instrument often accompanies poetry recitations, historical ballads, and religious gatherings.

There is a common belief in some regions that the instrument carries blessings or protective qualities, particularly when played during communal celebrations. This belief does not depend on formal religion but on shared cultural memory.

Historically, offering a hitaar to a guest musician was considered a gesture of honor. Owning a finely crafted instrument symbolized not wealth but cultural refinement.

Even today, elders often encourage young musicians to learn hitaar not for commercial success but for cultural continuity. In this way, the instrument becomes a bridge between generations.

Urbanization has reduced the number of communal performances, yet cultural festivals and heritage programs continue to include hitaar ensembles, reinforcing its place in collective identity.

Comparative View of Hitaar Among Stringed Instruments

| Instrument | Region of Origin | Typical Strings | Primary Cultural Role | Construction Style |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hitaar | Middle East and South Asia | 5–8 | Rituals, storytelling, folk and court music | Handcrafted |

| Guitar | Europe (Spain) | 6 | Popular and classical music | Mass-produced and handcrafted |

| Sitar | Indian subcontinent | 18–21 | Classical performance | Highly specialized handcrafted |

| Oud | Middle East | 11–13 | Classical and folk traditions | Handcrafted |

This comparison shows that hitaar occupies a middle space between complexity and accessibility. It is less structurally elaborate than sitar, yet more culturally specialized than the guitar.

Modern Transformations and Digital Revival

In the last two decades, hitaar has experienced a subtle revival driven by digital communication rather than state institutions. Musicians share performances online, document building techniques on video platforms, and collaborate across continents.

Recording studios increasingly experiment with hitaar as a texture instrument, blending its warm tone with electronic music, ambient compositions, and film soundtracks. Some producers describe its sound as “organic compression,” meaning it sits naturally within digital mixes.

Instrument makers have responded by creating hybrid models with internal microphones, removable pickups, and reinforced bodies designed for travel. These designs allow traditional sound to coexist with modern performance environments.

Educational initiatives also contribute to preservation. Online tutorials and digital archives store tuning systems and performance styles that were once transmitted only in person.

In this sense, hitaar becomes a form of cultural software: an analog technology maintained through digital infrastructure.

Expert Perspectives on Cultural and Musical Significance

“Hitaar represents an uninterrupted thread of musical knowledge that predates written theory,” says Dr. Amina Rashid, an ethnomusicologist specializing in Middle Eastern traditions. “Its value lies not only in sound but in the way it encodes social relationships.”

Omar Al-Farouq, a master luthier, emphasizes craftsmanship. “Each instrument teaches you how to listen to wood. There is no blueprint that replaces experience.”

Music historian Sara Patel highlights adaptation. “When young musicians integrate hitaar into experimental genres, they are not diluting tradition. They are expanding its grammar.”

These perspectives reinforce the idea that hitaar survives because it evolves carefully rather than remaining static.

Challenges of Preservation

Despite renewed interest, hitaar faces structural threats. Traditional apprenticeship systems are shrinking. Many young people pursue careers unrelated to craftsmanship or music.

Mass-produced instruments dominate global markets, reducing demand for handmade alternatives. Without sustained cultural investment, knowledge risks becoming fragmented.

Organizations dedicated to cultural heritage attempt to document building methods and musical styles. Workshops, festivals, and digital archives aim to ensure continuity.

Preservation, however, requires more than documentation. It requires living practitioners who see value in the slow process of making and learning.

Timeline of Hitaar’s Cultural Development

| Period | Development |

|---|---|

| Pre-1500 | Emergence from earlier regional chordophones |

| 1600–1800 | Integration into court and ceremonial music |

| 1800–1950 | Spread through rural folk traditions |

| 1950–2000 | Decline due to modernization |

| 2000–present | Digital revival and fusion experimentation |

Takeaways

- Hitaar is a traditional stringed instrument rooted in Middle Eastern and South Asian culture.

- Its craftsmanship relies on manual carving and acoustic intuition.

- Performance emphasizes modal systems and improvisation.

- The instrument plays a central role in rituals and storytelling.

- Digital platforms have enabled global rediscovery.

- Preservation depends on living artisans and musicians.

Conclusion

Hitaar survives not because it resists change, but because it adapts without forgetting itself. It remains carved from wood, tuned by hand, and learned through listening, even as its sound travels through digital networks and modern studios.

In many ways, hitaar mirrors the broader human relationship with technology. It is both tool and story, both object and practice. It reminds us that innovation does not always require replacement. Sometimes it requires careful extension.

For a publication like Git-Hub Magazine, which often examines how systems evolve, how tools carry ideology, and how design shapes culture, hitaar offers a powerful metaphor. It is a legacy system that continues to receive meaningful updates without erasing its original code.

As long as hands continue to carve, tune, and play, the instrument will remain more than a museum artifact. It will remain a conversation between generations.

FAQs

What is hitaar?

Hitaar is a traditional stringed instrument used in folk, ceremonial, and historical music across parts of the Middle East and South Asia.

How many strings does it have?

Most traditional versions use between five and eight strings, depending on regional design.

Is hitaar still used today?

Yes. It appears in cultural festivals, private performances, recordings, and experimental music projects.

Is it difficult to learn?

Like most traditional instruments, it requires patience, but beginners start with basic tuning and plucking techniques.

Why is hitaar culturally important?

It carries historical memory, craftsmanship knowledge, and community identity across generations.