Air France A350 Chicago Flight Return Explained

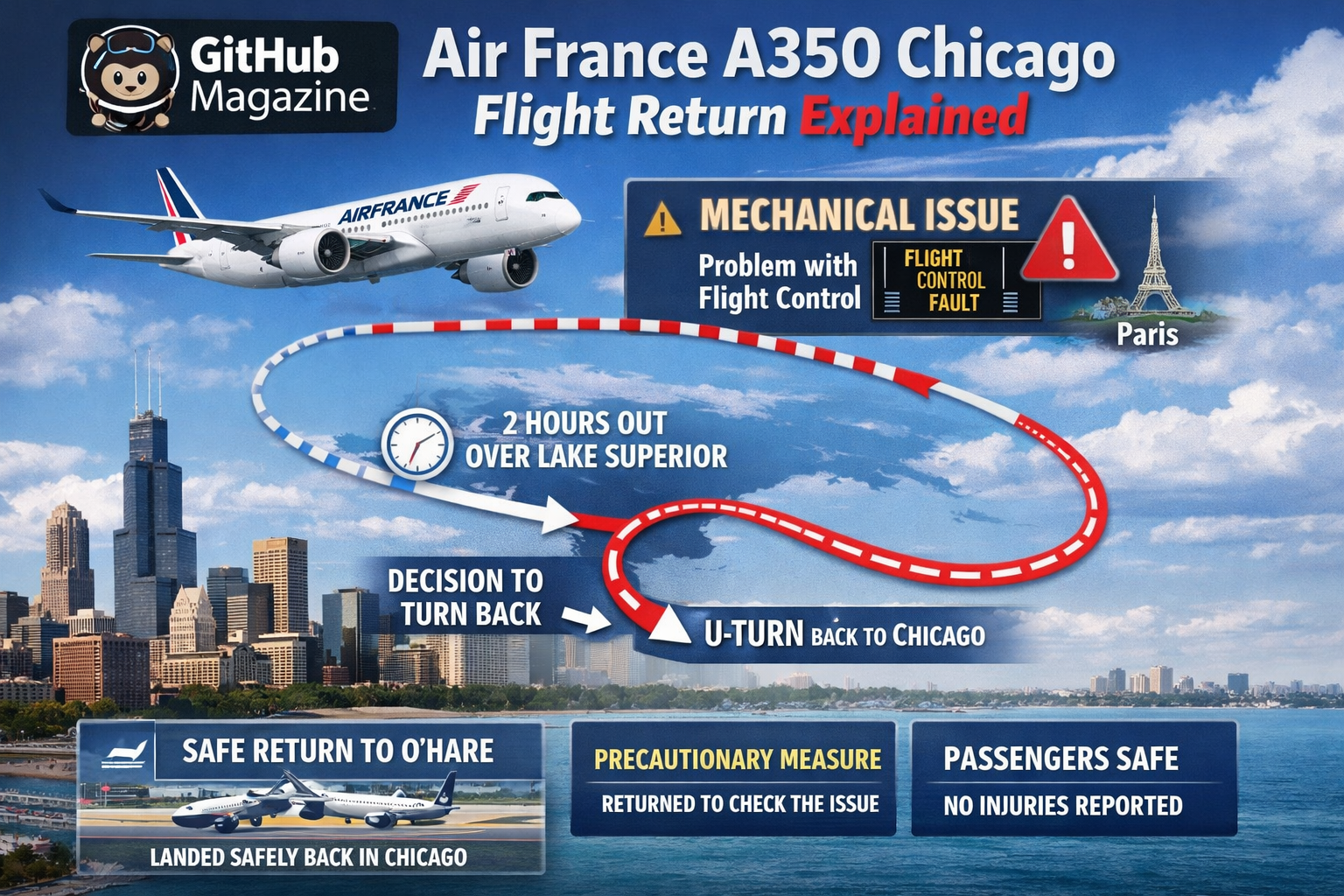

In late June 2025, an Air France Airbus A350 left Paris for Chicago as it had done hundreds of times before. The route was routine, the aircraft modern, the skies calm. Yet seven hours later, instead of descending toward Lake Michigan, the jet pointed east again, retracing its path across the Atlantic and returning to Charles de Gaulle Airport. For passengers, the experience felt surreal. For the airline, it was an operational shock. For the aviation industry, it became a rare example of how a single regulatory omission can outweigh fuel, technology, weather, and even geography.

The reason, according to industry reporting and airline operations analysis, was not mechanical failure or medical emergency, but documentation and landing clearance tied to the aircraft’s registration. The aircraft itself was healthy. The crew was qualified. The weather cooperated. Only the digital and regulatory architecture that governs international arrivals failed to align in time.

Within aviation circles, this incident quickly became shorthand for how vulnerable global mobility is to invisible systems: customs databases, flight manifests, border-security protocols, and the quiet handshake between airline operations centers and government agencies. This article examines what happened aboard Air France Flight AF136, how the Airbus A350 fits into modern long-haul aviation, why such returns are almost unheard of, and what this moment reveals about the technological scaffolding behind international travel.

Operational Anatomy of the AF136 Return

Flight AF136 departed Paris–Charles de Gaulle in the early afternoon, scheduled to arrive at Chicago O’Hare in the early evening local time. The aircraft, an Airbus A350-900, climbed smoothly to cruising altitude and joined the organized lattice of North Atlantic Tracks, the invisible highways that guide transoceanic traffic. Passengers settled into movies, meals, and sleep.

Several hours later, somewhere between Ireland and Newfoundland, the cockpit received word from airline operations: the aircraft did not hold confirmed landing clearance in the U.S. system for that specific registration. Under American customs and border procedures, every arriving aircraft must be logged in advance, with its tail number matched to crew and passenger manifests. Without that clearance, the aircraft could land physically but not legally complete the arrival process.

Airlines typically resolve such issues before departure. When discovered mid-flight, the options narrow to diversion or return. Diverting to another European airport would still require re-processing the flight, crew duty limits, and regulatory coordination. Continuing to Chicago without clearance would risk regulatory penalties and operational chaos on the ground. The safest procedural choice was to return to Paris, where maintenance crews, immigration facilities, and replacement aircraft were immediately available.

The captain announced the decision to passengers with careful neutrality. The aircraft banked slowly eastward. Screens showing the flight map revealed the reversal before words fully settled into meaning.

The Aircraft: Why the A350 Matters

The Airbus A350 is among the most advanced commercial aircraft ever built. Air France introduced it to modernize long-haul routes with lower fuel burn, quieter cabins, and advanced digital monitoring. On the Paris–Chicago route, the type symbolizes reliability and efficiency, not improvisation.

| Feature | Airbus A350-900 |

|---|---|

| First commercial service | 2015 |

| Typical seating (Air France) | 300+ passengers |

| Range | ~8,100 nautical miles |

| Primary material | Carbon-fiber composites |

| Engines | Rolls-Royce Trent XWB |

| Route role | Long-haul transatlantic backbone |

The aircraft constantly transmits performance data to airline servers, predicting maintenance needs before faults appear. Yet none of this technological sophistication can override immigration law or customs databases. The A350 can cross oceans more efficiently than any jet before it, but it cannot bypass administrative reality.

Regulation as the Invisible Airspace

Every international flight exists in two parallel skies: the physical atmosphere and the regulatory environment. Pilots navigate jet streams and turbulence, but airline operations navigate treaties, customs codes, and digital clearance systems.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection requires advance electronic transmission of passenger data, crew credentials, and aircraft identifiers. These systems are designed for security and efficiency, but they are unforgiving. A mismatched tail number or delayed approval can halt an arrival as effectively as a closed runway.

Dr. Gillian Turner, an aviation law scholar, describes the process as “a choreography of databases.” One missed step, she explains, “forces airlines into conservative decisions because international aviation tolerates no gray zones at the border.”

This rigidity is intentional. Aviation security depends on predictability. But predictability can also magnify minor errors into dramatic outcomes, such as a jet turning around halfway across an ocean.

Inside the Cabin: Human Time Versus System Time

For passengers, the return collapsed two different experiences of time. Airline systems measure minutes and deadlines. Travelers measure birthdays missed, hotel reservations lost, meetings postponed.

Accounts from passengers described initial confusion, then resignation. Cabin crew distributed water and attempted to answer questions with limited information. Children cried. Business travelers typed urgent emails. Some passengers laughed in disbelief. Others stared silently at the seat in front of them, watching hours dissolve.

Air France later arranged hotels, rebookings, and meal vouchers. Yet compensation does not restore a sense of narrative order. Travelers expect turbulence, not reversals of destiny.

How Rare Is a Mid-Ocean Return?

Commercial flights divert daily. They return to departure airports only a handful of times per year worldwide. A mid-Atlantic reversal is rarer still.

| Airline | Typical response to regulatory issue | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Air France | Return to hub | Extremely rare |

| Lufthansa | Diversion or return | Rare |

| British Airways | Diversion | Rare |

| American Airlines | Diversion | Occasional |

Captain Mark Dunham, a former transatlantic pilot, notes that returning is often the most conservative option. “When you’re uncertain about what will happen on the ground,” he says, “you choose the environment you understand best.”

Simone Leclerc, an airline operations analyst, adds that airlines design procedures to avoid improvisation at foreign hubs. “Returning home allows the airline to reset every variable.”

Technology That Could Not Save the Day

Air France, like most global carriers, relies on interconnected software platforms to coordinate crews, aircraft, fuel planning, immigration compliance, and passenger data. These systems are robust, but not infallible.

In recent years, airlines have suffered from outages caused by cloud failures, cyberattacks, and human error. The AF136 incident did not involve a crash or hack, but it revealed how a single overlooked data point can ripple outward.

Expert quote, aviation systems engineer Laura Chen: “We talk about airplanes as machines, but airlines are really data companies that happen to fly aircraft. When the data fails, the airplane becomes irrelevant.”

Expert quote, transportation policy analyst Javier Morales: “Regulators assume digital perfection. Airlines live in a world of imperfect human processes layered onto perfect legal expectations.”

Expert quote, airline safety consultant Robert Hayes: “The system worked, even if the outcome was painful. The aircraft did not land illegally. That is success by regulatory standards.”

Economic and Environmental Cost

Turning an A350 around mid-flight burns tens of thousands of kilograms of additional fuel. It also disrupts crew schedules, aircraft rotations, and passenger itineraries.

| Impact Area | Approximate Effect |

|---|---|

| Additional fuel burned | 40–60 tons |

| Carbon emissions | Hundreds of tons CO₂ |

| Passenger delay | 12–24 hours |

| Aircraft availability | One full day lost |

| Crew duty extensions | Multiple reassignments |

Airlines accept these costs because regulatory violations could be worse: fines, loss of landing rights, reputational damage, or intensified scrutiny from authorities.

Why Not Divert to Another Airport?

To outsiders, diverting to London or Dublin may seem simpler. In practice, diversion creates cascading problems. Crew duty limits may expire. Maintenance teams may lack parts. Passenger immigration processing becomes complicated. Repositioning the aircraft can take days.

Returning to Paris centralized control. It allowed Air France to deploy another aircraft, reset documentation, and restore schedule stability.

Aviation Culture and the Weight of Procedure

Modern aviation is built on checklists. Pilots train to trust procedures even when instincts protest. The AF136 return demonstrated this culture in action. No heroics. No shortcuts. Only adherence to protocol.

In a world that celebrates speed and disruption, aviation remains stubbornly conservative. Its safety record depends on that conservatism.

Takeaways

• International flights operate inside strict digital and legal frameworks invisible to passengers.

• The Airbus A350’s technology cannot override regulatory requirements.

• Mid-flight returns are rare but illustrate aviation’s procedural culture.

• Data systems are as critical as engines in modern airlines.

• Passenger experience often collides with institutional caution.

• Environmental and economic costs are secondary to legal compliance.

Conclusion

The Air France A350 that turned back from Chicago never malfunctioned. It never entered turbulence worthy of headlines. It simply encountered a wall made of paperwork. In doing so, it revealed how aviation has evolved from daring mechanical adventure into a discipline of databases and decisions.

Passengers will remember wasted hours and disrupted plans. Engineers will remember a system that did what it was designed to do. Regulators will see confirmation that borders remain firm even at cruising altitude.

In the end, the aircraft landed where it began, its journey folded neatly back into itself. The ocean it crossed twice remained indifferent. The lesson, however, traveled farther: in global aviation, the most powerful force is not wind or steel, but procedure.

FAQs

Why did the flight return instead of continuing to Chicago?

Because the aircraft lacked confirmed landing clearance in U.S. customs systems, making arrival legally impossible.

Was the aircraft unsafe?

No. The A350 had no technical problems and was fully operational.

Do such returns happen often?

They are extremely rare, especially over oceans.

Could passengers claim compensation?

Typically airlines provide rebooking, hotels, and sometimes financial compensation depending on regulations.

Did this affect other Air France flights?

Indirectly, through aircraft and crew rescheduling, but operations normalized within days.